Higher Purpose

Achieving Self-Actualization

The Foundation: Self-Actualization & Motivation

Self-actualization is much more than a grand, abstract concept. It is a way of being that can manifest in practical daily actions. It is the very essence of who we are, or more accurately: who we will become.

Self-actualization, in a nutshell, is an ongoing motivational drive that we all have to grow and fulfill our talents and potential.

Self-actualization can mean different things to different people and it can take many forms; for example, a musician would pursue music, an artist would pursue painting, a researcher would pursue knowledge in an uncharted territory. But self-actualization need not be confined to a specific talent. A mother desiring to be an ideal mother seeks to apply genius and creativity to child-rearing. She might also be an accomplished musician, a talented artist and the founder of an organization devoted to social justice. Self-actualization is never exactly the same for any two human beings.

Self-actualization is most often discussed in terms of the theory originally proposed in 1943 by renown humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow. His theory sought to explain how humans prioritize innate, universal motivational needs. At the time, it was revolutionary to propose that rather than being motivated by some deep-seated need to compensate for our physical or psychological deficits, we actually yearn to evolve beyond satisfying our basic biological and emotional needs, to actualize our full individuality, and connect with all of humankind and to the universal consciousness. It is a positive, optimistic view of human nature that considers what’s right with a person’s psyche, rather than what’s wrong with it.

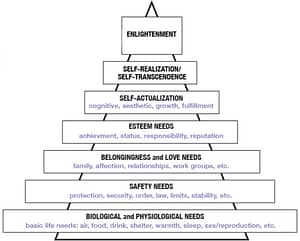

Maslow proposed that a human being’s motivational needs naturally formed a hierarchical pyramid, from the most primitive to the most advanced:

- Biological and Physiological — basic life needs: air, food, drink, shelter, warmth, sex, sleep

- Safety — protection, security, order, law, limits, stability

- Belongingness and Love — family, affection, relationships, work group

- Esteem — self-esteem, achievement, status, responsibility, reputation

- Self-Actualization — personal growth and fulfillment, realizing personal potential, peak experiences

So far, so good. But Maslow also believed that it was only when our first four basic biological emotional needs are met, are we motivated to pursue self-actualization. And therein lies the problem. As the century wore on, the order of development in Maslow’s hierarchy of was sometimes at odds with modern thinking, including neuropsychological evidence, for example, that could show precisely what our motivation was, in any given moment.

It’s true that some motives take cognitive priority and developmental priority over others. Developmentally speaking, our priorities generally do tend to shift from lower to higher in the hierarchy as we mature, though we all mature at different rates. It’s also true that if every waking hour is devoted to achieving the lower four levels, we may have little motivation to achieve — or even have little awareness of — the higher reaches of personal growth. But if we’re hungry and in danger, our first priority is not self-actualization. It’s food and safety. And if we haven’t known love or developed profound interpersonal relationships, we’re not likely to have the deep knowledge, acceptance and understanding of human nature that would allow us to contemplate and, ultimately, actualize our desire for unity, integration and synergy within. So, it’s probably fair to say that if we are not able to consistently satisfy the three lower levels, we are not free to fulfill our potential, for the psyche is not mature enough or developmentally advanced enough to do so.

So, as for the fourth level of esteem, must we have a sense of responsibility, self-esteem and self-respect to pursue self-actualization? In general, yes. But must we have gained the respect of others, achieved a certain social status or “built a reputation” to become self-actualizing? Not necessarily. Pursuing the fulfillment of our unique talent potential may be experienced separately from the pursuit of esteem, even though the two pursuits are rooted in a common motivational system (Kenrick et al, 2011). Our cognitive priorities and developmental priorities do not always move in perfect synchrony which each other. Sometimes we try to fly before we can walk. Sometimes we’re still walking when we should be flying.

Personal development is an ongoing dynamic interaction between our internal motives and external environmental opportunities and threats. Anything we perceive to be a threat can activate lower motivational drives, thus the cognitive hierarchy may change dynamically with context at any point in our lives. Even highly self-actualized people who are normally motivationally focused on higher matters, will shift their primary focus to food if they’re truly starving.

On the flip side, it is certainly possible for the higher motivation of self-actualization to emerge as the dominant motivation in people who have not firmly resolved the lower needs for survival, safety, etc. (Koltko-Rivera, 2006). Teenagers or even adolescents with relatively high emotional maturity who would be unable to meet their own basic survival and safety needs might begin pursuing paths toward self-actualization. The difference is that without autonomy and a sufficient degree of cognitive and emotional maturity, the degree of self-actualization or self-transcendence they can realistically achieve at that stage of development would be limited; that is, they cannot achieve the peaks of actualization without first achieving maturity.

But there’s another way to look at it. Self-actualization can provide an alternative pathway to high esteem. After all, the more self-actualizing one is, the higher one’s esteem is likely to be.

But is self-actualization all there is? Is it truly the pinnacle of human motivational development?

In his final years, even Maslow didn’t think so. His investigation of the “farther reaches of human nature,” including the meditative practices of Buddhist monks, would lead him to add a sixth motivational level that, interestingly, is rarely mentioned, a level that transcends self-actualization: Transpersonal/Self-Transcendence.

The Transpersonal level is driven by inspiration, self-transcendence, a full spiritual awakening or liberation from egocentricity, and a need to help others to achieve self-transcendence (Maslow, 1970b; Privette, Bundrick, 1991). Self-transcendence is closely aligned with the concept of self-realization, which is one of the primary goals of meditation. (For more about self-realization, see Self-Realization.)

Other humanistic psychologists such as Carl Rogers, Gordon Allport, Carl Jung and others inserted motivational levels such as Cognitive (knowledge, meaning, self-awareness) and Aesthetic (beauty, balance, form) between Esteem and Self-Actualization, but Maslow folded these characteristics into the realm of self-actualization.

For the purposes of this website and discussing how Sahaja meditation influences human motivation, a modern view of human motivational needs might look something like this:

Despite its flaws in imposing a strict, universal order of development, Maslow’s concept of prioritized motivations and his research into the characteristics of self-actualization still have relevance today.

References

Douglas T. Kenrick, Vladas Griskevicius, Steven L. Neuberg, and Mark Schaller. Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations. Perspect Psychol Sci. PMC 2011 August 25.

Koltko-Rivera, Mark E.. Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification. Review of General Psychology, 2006, Vol. 10, No. 4, 302–317.

Maslow, A.H. (1970a). Motivation and Human Personality (rev ed.). New York: Harper.

Maslow, A. (1970b). Religions, values, & peak experiences. New York: Viking.

Maslow, A.H. (1971). The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Viking.