Emotional Intelligence

EI in Relationships

EI’s Impact on Personal and Marital Relationships

It’s not hard to accept the idea that higher emotional intelligence (EI) creates higher quality relationships. After all, you never hear of someone leaving a marriage because his or her partner was too supportive, too understanding and too attentive to their needs. But the simplicity of these statements is deceptive.

In real life, especially in the most trying moments, being able to understand your partner’s needs and feelings and exercise empathy, patience and self-control often requires a combination of sophisticated emotional skills. The repertoire of special emotional abilities required to successfully negotiate relationship ups and downs suggests that if ever there were a natural fit for emotional intelligence, it’s in “couples” relationships.

Emotional intelligence can manifest in idiosyncratic ways in any one relationship, but could be summarized as the capacity to perceive, identify, express, understand, manage emotions in oneself and others and to use that information to assist thought and achieve life goals.

EI is the emotional-cognitive mechanism through which we reason with — and about — our feelings. And feelings are the very heart of the bond between two partners.

Each of us has certain emotional needs that must be fulfilled by our partners if our relationships are to survive, thrive and grow. You could think of these needs as essential emotional nutrients, the daily diet of nutrients required for good relationship health that partners can only obtain from each other.

Awareness is the foundation upon which all other EI abilities are built. Awareness includes the ability to identify the emotional nutrients you need, as well as the nutrients that your partner needs. Understanding? Respect? Honest communication? If you were to list your partner’s three most important emotional nutrients and your partner did the same, would the two lists match? If so, score one for your emotional intelligence.

Chances are, each of you met the others’ emotional needs when the relationship first began or the relationship would have never gotten off the ground. But as we grow and change, our emotional needs can change. The person with high EI will perceive the emotional sea changes in his or her partner. When we feel that our most important relationships help us grow, we’re motivated to keep them going. When we feel that they don’t support our needs, we aren’t. And that’s when relationships end.

Relationship Quality

The happiness of each partner and the durability of the relationship is dependent on the quality of the relationship. What constitutes “quality?” No doubt you have your own ideas about what a quality relationship is, but certainly, most any list would include mutual goals, trust, affection, respect and emotional support; the ability to manage stress and resolve conflicts; and the feeling of being understood, even when no words are spoken.

We often hear about the “top reasons” that marriages dissolve… infidelity, finances, religion, sexual compatibility, et cetera, but it may surprise you to learn that the emotional forces at work between husband and wife — their collective reservoir of emotional intelligence — have been found to have more impact on the quality of a marriage than the usual suspects (Fitness, 2000; 2001). A Pakistani study of married couples found that five aspects of emotional intelligence (emotional assertiveness, interpersonal skill, optimism, empathy, impulse control) predicted the quality of the marriage (Batool, Khalid, 2012) and conflict resolution.

A review of American and European studies found that emotional expressiveness and communication were the two most important contributing factors to marital quality and conflict resolution, followed by empathy, self-awareness and impulse control (Batool, Khalid, 2009b).

What special emotional abilities improve the quality of relationships among couples?

For starters, the quality of our relationships is directly related to our ability to form secure attachments or affectional bonds to others. And our level of emotional intelligence directly impacts our ability to become securely attached to others — it’s a bidirectional relationship.

Notice: Undefined index: main_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 33

Notice: Undefined index: blue_rich_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 35

Notice: Undefined index: blue_rich_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 108

How EI Influences our Ability to Form Secure Attachments

Attachment is that special emotional bond between two people that provides comfort and safety. It is a lasting psychological connectedness. Our secure base. Our safe haven in times of illness, danger or distress.

Our ability to form these close bonds with other humans throughout our lives follows a pattern: an attachment style. Various attachment theories have been debated over the years, but a widely accepted contemporary approach to adult attachment styles is the model proposed by Kim Bartholomew and Leonard Horowitz (Bartholomew, Horowitz, 1991), which reflects our views across two dimensions: our internal view of ourselves; our internal view of other people.

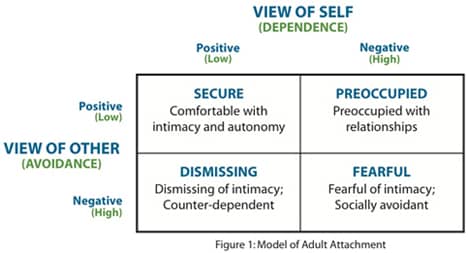

This model, reflected in the four cells in Figure 1 below, revolves around the idea that one’s view of oneself is either generally positive or negative (i.e., the self is viewed as worthy of love and that support or not) and one’s view of others (e.g., a partner) is either generally positive or negative (e.g., trustworthy and available vs. unreliable and rejecting). Thus, there are four combinations or attachment styles: Secure and three Insecure styles: Dismissing, Preoccupied and Fearful.

The following statements describe each of the four attachment styles (Bartholomew, Horowitz, 1991)…

Secure

- It is relatively easy for me to become emotionally close to others. I am comfortable depending on others and having others depend on me. I don’t worry about being alone or having others not accept me.

Insecure

- Dismissing. I am comfortable without close emotional relationships. It is very important to me to feel independent and self-sufficient, and I prefer not to depend on others or have others depend on me.

- Preoccupied. I want to be completely emotionally intimate with others, but I often find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I am uncomfortable being without close relationships, but I sometimes worry that others don’t value me as much as I value them.

- Fearful. I am somewhat uncomfortable getting close to others. I want emotionally close relationships, but I find it difficult to trust others completely, or to depend on them. I sometimes worry that I will be hurt if I allow myself to become too close to others.

Our everyday emotional information processing and reactions are deeply influenced by our attachment style. Our attachment styles integrate both the emotional and cognitive rules and strategies that drive the emotional dynamics of our relationships and, ultimately, the evolution of our emotional intelligence (Collins, 1996).

People with a secure attachment style have positive internal views of both self and others and are comfortable with intimate relationships.

They have a sense of worthiness (lovability), a basic belief that they’re deserving of support from others and an expectation that other people are generally accepting and responsive and will help them when needed.

Each of the insecure (preoccupied, fearful, and dismissing) attachment styles, however, has its own distinctive set of interpersonal problems, which inevitably manifest in our most intimate relationships. The emotional defenses associated with insecure attachment block our awareness of feelings in ourselves and others and inhibit our ability to process emotional messages (Bowlby, 1988). In other words, an inability to form secure attachments blocks emotional intelligence and vice versa: people with low EI have less ability to form secure attachments. (For an in-depth look at defense mechanisms, see: Playing Defense: Where Defense Mechanisms Come From and How to Know When They’re Hurting You.)

The attachment styles depicted in Figure 1 can also be understood in terms of a person’s level of dependency on others (horizontal axis) and his or her avoidance of intimacy (vertical axis). Avoidance of intimacy reflects the degree to which people avoid close relationships because they fear disappointment, rejection or negative consequences. People with low dependency have high self-respect and don’t require external validation by others. But in people who are highly dependent, self-respect can only be maintained through ongoing acceptance by others. (For a better understanding of self-respect and self-esteem, see the Self-Esteem Guide – 7 Popular Myths About Self-Esteem and How Sahaja Meditation Builds Healthy Self-Esteem.)

Insecure attachment types can be characterized as follows (depicted in Figure 1 below):

- The preoccupied attachment type has a negative view of self and a positive view of others. The preoccupied type has a sense of unworthiness (unlovability) combined with a positive evaluation of others, which often causes ambivalence and anxiety that compels them to strive for self-acceptance by gaining the acceptance of valued others. They tend to be preoccupied with — and feel anxious about — their relationships and are heavily dependent on others. Highly preoccupied individuals are often angry, jealous and combative and prone to feeling that their partners are insensitive to their needs (Collins, 1996). They tend to invest too much energy in relationships that aren’t in their best interests.

- The fearful attachment type (fearful-avoidant) has negative internal views of both self and others. They have a sense of unworthiness (unlovability) combined with an expectation that others will treat them in some negative way (e.g., untrustworthy or rejecting). They are socially avoidant, avoiding intimate relationships with others to protect themselves against anticipated rejection. They fear that others will hurt them and believe that they don’t deserve to be treated well due to their perceived personal shortcomings.

- The dismissing attachment type (dismissive-avoidant) has a positive view of self and a negative view of others. They have a general sense of love-worthiness combined with a generally negative view of others. They are socially avoidant, often seen as emotionally aloof. They protect themselves from disappointment by avoiding close relationships. They place little value on intimacy and may even deliberately refuse to attach. They choose independence and autonomy over the healthy interdependence that comes with good relationships, thus they are counter-dependent.

Dismissings and fearfuls are alike in that both avoid intimacy; however, fearful people need others’ acceptance to maintain self-respect; dismissing people don’t. Preoccupieds and fearfuls are alike in that both strongly depend on others to maintain self-respect but differ in their willingness to become involved in close relationships. Preoccupied people reach out to others in an attempt to fulfill their dependency needs, while fearful people avoid closeness to minimize anticipated disappointment.

Another way to view the four attachment types is through the two dimensions of anxiety and avoidance, as illustrated in Figure 2 below (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994).

You can see that the more secure we are, the less anxious we are, the less avoidant we are (e.g., avoiding a partner’s gaze or engaging in the blame game), and the less we depend on others to maintain a sense of self-worth. Why? We have positive views of both ourselves and others, whereas, fearful people have high anxiety because they have negative views of both self and others. Preoccupied people have high anxiety because they have a negative view of self. Dismissives have lower anxiety because they have a generally positive view of self, but tend to be highly avoidant because they have a generally negative view of others.

Studies have revealed how both relationship quality and attachment style correlate with one’s level of emotional intelligence. Numerous studies, for example, have shown that happy marriages are associated with: positive emotions (Gottman, Levenson, 1992), emotional stability (Russell, Wells, 1994), self-esteem (Arrindell & Luteijn, 2000; Luteijn, 1994), and secure attachment style (e.g., Feeney, 1999).

How does attachment style connect to relationship EI?

Here’s what the science shows…

First, emotional self-regulation, a key element of EI, functions within our attachment style. (For more about how Sahaja meditation helps regulate emotion, see: Sahaja Meditation as Emotional Regulator.) As you might guess, secure people have very different strategies for processing, expressing and regulating emotion than people with one of the three insecure attachment styles.

Secure partners use emotional regulation strategies that minimize stress and emphasize positive emotions. Insecure partners, on the other hand, not only tend to experience more negative emotions but also experience events more stressfully (e.g., anxiety attachment, excessive neediness or nagging).

Or they tend to avoid intimacy through defense mechanisms such as suppressing those emotional experiences (avoidant attachment) (Kafetsios, 2004; Searle and Meara,1999).

The ability to perceive emotions in ourselves and in our relationship partners is highly correlated with our attachment orientation. Secure individuals have been found to be more accurate than avoidant (dismissing and fearful) people at decoding their spouses’ emotions, including nonverbal behaviors (e.g., facial expressions), especially those that signify joy (Kafetsios, 2004). You can imagine that intimate relationships are especially challenging for people who don’t possess the very basic ability to determine whether their partners are happy.

People with an anxious attachment orientation (fearful or preoccupied) also struggle to decode positive nonverbal behaviors in their partners (Feeney, Noller, & Callan, 1994). And as you might guess, fearful and preoccupied people also experience higher levels of emotional intensity than secure or dismissing people. Dismissing-avoidant people seem to handle emotions more effectively than fearful-avoidant people, but presumably because they’re concerned about promoting their own personal wellbeing (Fraley & Shaver, 2000).

Both secure and preoccupied-anxious people pay more attention to their partners’ emotional messages and feel them more intensely than fearful-avoidant or dismissing-avoidant people (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). Secure people use that emotional information to guide their actions; preoccupied people pay attention because they heavily depend on others for feedback and validation.

But one study showed that fearful-avoidants and dismissing-avoidants, desperate to minimize attachments that might make them feel vulnerable, may self-regulate by literally excluding attachment-related emotional experiences from awareness; i.e., isolating them from memory (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). This is problematic because two key elements of EI — emotional understanding and using emotion to facilitate thought — rely heavily on memory to prioritize problems and solutions and categorize or label emotional messages.

Fearfuls and dismissings have been shown to suppress memory through both preemptive and postemptive defense strategies. Preemptive strategies minimize attention to events that have the potential to activate unwanted thoughts or feelings, limiting the amount of information that’s ever encoded in memory (which would later have to be painfully reexperienced). For example, they may avoid getting involved in a close relationship for fear of rejection, or they may ‘‘tune out’’ of a conversation that touches upon attachment-related themes. Postemptive defense strategies exclude emotional information from awareness by failing to retrieve, dwell upon, or find meaning in past experiences that were already encoded in memory. For example, following a breakup or death of a partner, an avoidant person may suppress memories of his or her former partner in order to avoid the reemergence of painful emotions. Postemptive defenses tend to be less effective than preemptive ones because once unwanted emotional information is encoded into memory, it becomes a source of vulnerability with the potential to undermine the person’s self-reliant facade.

It’s true that such defense strategies may help someone avoid pain, but they’re sure to leave that person’s partner feeling dissatisfied or uncomfortable. Avoidance, or the failure to attend to attachment-related experiences, prevents us from ever having a deep, rich, or sophisticated emotional life.

One 2005 study of relationship quality in couples explored the connections between attachment style and four primary dimensions of emotional intelligence — emotional perception and understanding, using emotion to facilitate thought, and managing emotions (Brackett, 2005). Relationship quality was measured through questions such as… How often does this person make you feel very angry? To what extent can you turn to this person for advice about problems? Relationships with low EI were found to have greater conflict and lower emotional depth, support, satisfaction and relationship quality.

In another study that investigated how attachment style and emotional intelligence interacted across the life of a relationship, secure attachment, not surprisingly, was highly correlated with the ability to understand and manage emotions (Kafetsios, 2002). Preoccupied-avoidants were found to have low EI, especially in the category of perceiving emotions. Interestingly, dismissing-avoidants were found to have strong cognitive or intellectual understanding of emotions — both changes (emotional progressions over time) and blends (how emotions combine to form other emotions; e.g., anger can lead to bitterness and resentment).

But being able to label emotions is not enough. It is only through allowing ourselves to feel emotions and use them to guide our lives that we live fulfilled lives.

If you’re curious about gender and age differences in EI abilities, several studies of couples have shown that females have significantly higher EI than male participants, especially in the dimensions of emotion perception and using emotion (Brackett et al, 2004; Kafetsios, 2004; Mayer et al, 1999). Older individuals have been found to have higher EI in three out of four dimensions of EI — facilitation, understanding and management of emotions (Kafetsios, 2004).

Notice: Undefined index: main_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 33

Notice: Undefined index: blue_rich_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 35

Notice: Undefined index: blue_rich_content in /home/748059.cloudwaysapps.com/znxvfcncpw/public_html/wp-content/themes/sahaja/pages/internal-page.php on line 108

Conflict Management

Complex and profoundly personal emotions like anger, resentment, guilt, jealousy and love are played out over time between two partners. Divorce studies reveal two common patterns that predict when a couple will divorce: the emotionally volatile attack-defend pattern, which predicts earlier divorce, and the emotionally inexpressive pattern, which predicts later divorce (Gottman, Levenson, 1992). What’s missing in both patterns, of course, is emotional intelligence.

In our closest relationships, emotions can be contagious, spreading from one partner to the other. You might literally “catch” your partner’s feelings of anger, anxiety or depression. When both partners are experiencing negative emotions at the same time, each feeds the other and the air becomes more toxic, the relationship dynamic more volatile. But emotional contagion can also be a good thing: You can also be infected with your partner’s joy, optimism, confidence and enthusiasm.

The ability to regulate your own emotional arousal immunizes you from “catching” (or being influenced by) your partner’s negative emotions. You’re able to maintain proper emotional perspective during a conflict. And perspective is the first thing to go when both partners are simultaneously experiencing negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, frustration or fear.

Lack of perspective also tends to make us “dig in,” lock down, or slip into the sort of mental rigidity that prevents us from accurately, objectively appraising the situation and seeking constructive solutions. Somebody starts a shouting match. Somebody storms out of the house. But couples who can maintain perspective and emotional equanimity during conflict can safely steer their relationships to higher ground. They don’t become anxious just because their partners are anxious. They don’t shout back at a partner just because a partner shouted at them.

Happiness in relationships can depend upon each partners’ ability to constructively cope with conflict and to understand and manage negative emotions like anger, resentment and hate. Thus, higher EI can lead to better management of disagreements — large and small — which, in turn, improves relationship satisfaction (Fitness, 2001).

Higher EI, for example, can enable a couple to more effectively manage the delicate emotional negotiations involved in seeking and granting forgiveness.

Some studies of emotional intelligence in couples have suggested that the EI composition of the couple (e.g., two low-EI partners; or one high-EI partner and one low-EI partner) may matter more than the EI level of each partner individually. In other words, what may matter most is how much combined EI is available to the couple as a resource, rather than how much EI is available to each partner individually. In fact, some studies have suggested that if at least one partner has high EI, that may be enough to ensure that the couple can effectively manage conflict and maintain a positive long-term relationship (Brackett, 2005).

Conflicts inevitably surface in every relationship sooner or later. But high EI may enable intimate relationship partners to view conflict as a natural outgrowth of relationships and separate the partner from the problem. The secret of a healthy marriage is not the absence of conflict; rather, it’s the ability to effectively resolve those conflicts. Good conflict resolution skills have saved many a marriage. Ultimately, emotional intelligence is just good relationship policy.

References

Arrindell, W. A., & Luteijn, F. (2000). Similarity between intimate partners for personality traits as related to individual levels of satisfaction with life. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 29–637.

Bartholomew, K. & Horowitz, L.M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244.

Bartholomew, K. & Shaver, P.R. (1998). Methods of assessing adult attachment. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships, pp. 25-45. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Batool, S., Khalid, R.. Emotional Intelligence: A Predictor of Marital Quality in Pakistani Couples. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 2012, Vol. 27, No. 1, 65-88.

Batool, S. S., & Khalid, R. (2009b). Role of emotional intelligence in marital relationship. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 24(1-2), 43-62.

Bowlby, John (1988) A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. Routledge. London.

Brackett, Marc, Warner, Rebecca, Bosco, Jennifer. Emotional intelligence and relationship quality among couples. Personal Relationships, 12 (2005), 197–212. Printed in the United States of America.

Brackett, M. A., Mayer, J. D., & Warner, R. M. (2004). Emotional intelligence and its relation to everyday behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1387–1402.

Collins, N.L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 810-832.

Fitness, Julie. (2000, June). Emotional intelligence in personal relationships: Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects. Paper presented at the 2nd Joint Conference of ISSPR and INPR, Brisbane, Australia.

Fitness, Julie. (2001). Emotional intelligence and intimate relationships. In J. Ciarrochi, J. P. Forgas, & J. D. Mayer (Eds.), Emotional intelligence in everyday life (pp. 98–112). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Fraley, R.C., Shaver, P.R.. (2000) Adult Romantic Attachment: Theoretical Developments, Emerging Controversies and Unanswered Questions. Review of General Psychology. Vol., 4, No. 2, 132-154.

Fraley, R. C., Garner, J. P., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult attachment and the defensive regulation of attention and memory: examining the role of preemptive and postemptive defensive processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 816–826.

Gottman, J.M., Levenson, R.W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221-233.

Griffin, D., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 430-445.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524.

Konstantinos Kafetsios. Attachment and emotional intelligence abilities across the life course. Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 37, Issue 1, July 2004, Pages 129–145.

Luteijn, F. (1994). Personality and the quality of an intimate relationship. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 10, 220–223.

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27, 267–298.

Russell, R.J.H., Wells, P.A. (1994). Personality and quality of marriage. British Journal of Psychology, 85, 161-168.

Searle, B., & Meara, N.M. (1999, March). Affective dimensions of attachment styles; Exploring self-reported attachment style, gender, and emotional experience among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(2), 147-158.

Shaver, P. R., Belsky, J., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). The adult attachment interview and self-reports of romantic attachment: Associations across domains and methods. Personal Relationships, 7, 25-43.